Fort Warren is located on Georges Island, now part of Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area. Construction began in 1833 as part of the United States’ effort to strengthen coastal defenses as a result of how easily the British were able to blockade and even invade American cities during the War of 1812. This included successfully burning Washington, D.C., to the ground. Today you might wonder what’s so bad about that, but back in the early 1800s it started a national panic. This age of fort construction was termed the Third System of Coastal Defenses, and from 1816 through 1867, forty-two forts were built, all to protect the waterways leading into major cities.

Georges Island overlooks The Narrows, the only deep-water channel that leads into Boston Harbor, which is why it was chosen as the site for Fort Warren. The Narrows runs between Georges and Lovells islands and then around the northern end of Long Island. Forts were also built on Castle Island (Fort Independence) and Governors Island (Fort Winthrop). Both Castle and Governors islands have since been connected to the mainland with landfill. Fort Independence still stands, but Winthrop was torn down when Logan Airport was built (Governors Island was incorporated into the airport).

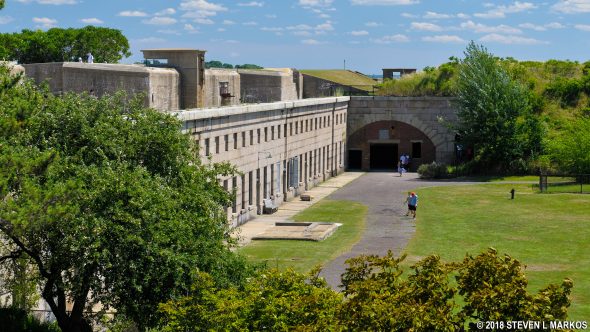

Basic construction of Fort Warren was completed in 1851. It was pentagon shaped with bastions at all corners, and though built to hold 334 guns, no funding was provided for weapons at the time of its completion. Other than one gun, the fort remained unarmed for another decade. It took the Civil War to break out in 1861 for guns to finally be installed, and even then it was never fully armed. The fort eventually held 200 guns, mainly 10-inch and 15-inch Rodman cannons, the largest artillery pieces of the time.

Fighting never came to Massachusetts during the Civil war, so Fort Warren served as a training ground for the first six months of the war before being converted into a prison camp. Casemates designed to hold artillery pieces were used as barracks. Inmates were Confederate soldiers, Union deserters, and political prisoners, including Alexander Stevens, the Vice President of the Confederacy who was held for five months after the war. As far as Civil War prison camps go, Fort Warren was one of the better ones, as only 13 prisoners died while in captivity. Two Union deserters were executed. Fort Warren continued as a prison until January 1866, eight months after the war ended.

Like all forts of its time, Fort Warren was a masonry fort built of stone, or in this case, granite from Quincy. The development of rifled artillery during the Civil War rendered masonry forts obsolete. Such forts had no problem stopping a cannonball, for these didn’t travel with much velocity, nor were they very accurate, so the chance of blasting a hole in a fort wall by hitting the same spot over and over again was slim. However, rifled artillery had an inner barrel with a spiral grove cut into it. When fired, bullet-shaped shells were sent spinning like footballs, increasing not only their accuracy, but also their range and velocity. The effect these shells had on masonry forts was first demonstrated during the Union bombardment of Fort Pulaski on April 10-11, 1862 (Fort Pulaski National Monument). The walls of the “indestructible fort” were breached in less than thirty hours, forcing the Confederates to surrender…and effectively ending the days of the masonry fortresses.

After the war ended, the United States government realized the vulnerability of the existing forts, but with much of the country in ruins, financially it was not able to do much about the situation other than outfit the forts with modern guns. It wasn’t until the threat of war with Spain came about in the 1880s that President Grover Cleveland formed a military commission to come up with ideas for coastal defense upgrades. The new system, initiated by Secretary of War William Endicott and referred to as the Endicott System of Coastal Defenses, called for the installation of small concrete and rebar batteries that could withstand the impact of the rifled shells. While much smaller than traditional forts, they were armed with guns that could damage the armor plated hulls of modern ships. Before the dawn of aviation, any invasion of the United States would most likely come from the sea.

Five batteries were installed on the grounds of Fort Warren between 1892 and 1902. Batteries Stevenson, Plunkett, and Adams replaced the northeastern wall of the fort, while batteries Bartlett and Lowell were installed on the grounds outside the fort. All of these exist today and range in condition from good to dilapidated. All but Battery Bartlett are open for exploration.

During World War I, Fort Warren served as a mine control center. Personnel were in charge of placing mines in Boston Harbor, all of which could be detonated from the fort via electric cables. Mines were stored in the building that now serves as the Georges Island Visitor Center. The building was constructed in 1906.

Original mine storage building, now the Georges Island Visitor Center, Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area

By the time World War II rolled around, only batteries Bartlett and Stevenson were still in use. However, the fort’s main purpose was once again that of a mine control station for the harbor. It was also during the war that most of the fort’s expansion occurred: barracks, mess halls, NCO and Officers’ quarters, etc.

With the advent of air warfare, long-range missiles, and advances in amphibious technology, stationary forts and batteries of all types became obsolete for defensive purposes. Many of the masonry forts were transformed into office space for the military or used as military schools and training facilities. Others were simply deemed expendable due to budgetary constraints and were closed. Fort Warren was one such fort. In 1946 it was decommissioned and fell into disuse.

After closing a number of military facilities in Boston Harbor after World War II, in 1957 the Federal Government put Georges and Lovells islands, along with the East Head area of Peddocks Island and a portion of Spectacle Island, up for auction. Massachusetts purchased Georges, Lovells, and Spectacle, while East Head was sold to Isadore Bromfield (the rest of the island remained privately owned). After basic restoration, Fort Warren was opened as a tourist attraction in 1961. In 1970 it was designated a National Historic Landmark, and five years later the island and fort became part of Boston Harbor Islands State Park. The park was subsequently incorporated into Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area in 1996.

Park Rangers and volunteers conduct tours of Fort Warren, and you can also walk around on your own. See the Touring Fort Warren web page here on National Park Planner for detailed information about the fort’s structure.

With a few exceptions, use of any photograph on the National Park Planner website requires a paid Royalty Free Editorial Use License or Commercial Use License. See the Photo Usage page for details.

Last updated on January 9, 2024