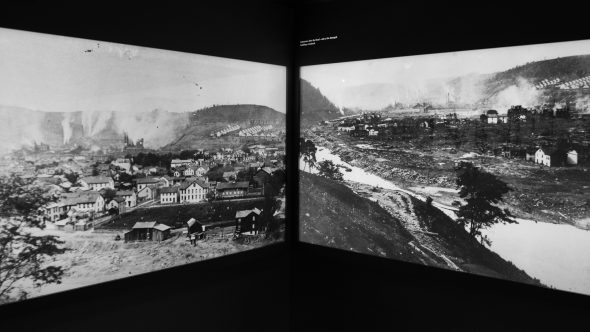

On May 31, 1889, two days after record heavy rain began, the dam that held back the waters of Lake Conemaugh, an artificial mountain lake created for the enjoyment of Pittsburgh’s elite, broke, sending a wall of water fourteen miles down the valley towards the industrial city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Over 2,200 people were killed in the ensuing disaster. To this day the Johnstown Flood remains the deadliest flood in American history and the third deadliest flood in the world due to a dam collapse.

In the early 1800s, promises of untold wealth lured people from the east to the new western frontier. Where people go, goods and services must follow, and all large northeastern seaboard cities wanted to be major players in the shipping of commodities and people to the navigable waters of the Great Lakes and the Ohio River, both gateways to the west. Likewise, the agriculture products produced on the fertile lands of the Midwest were in need of a faster way back to the heavily populated regions in the east.

The main problem that all northeastern cities faced was that there was no easy way to ship goods westward. In the early 1800s, wagons were the only choice, but the journey took nearly a month, and wagons could not hold a lot of cargo. While there were rivers that ran east to west, none were navigable, all having stretches of rapids, waterfalls, and low water. The solution would ultimately be canals: artificial and completely navigable waterways that could move boats loaded with cargo regardless of sloping terrain. Canals usually followed the non-navigable rivers and used them as their source of water.

The first state to finish a major canal was New York, which completed the Erie Canal in 1825. The canal ran from Albany to Buffalo on Lake Erie. Not wanting to lose the shipping business to New York, the state of Pennsylvania, with a major port in Philadelphia, decided to dig a canal of its own called the Pennsylvania Main Line. The western destination was Pittsburgh, which sat on the Ohio, Allegheny, and Monongahela Rivers. One canal would be dug from Philadelphia to Hollidaysburg, and another from Pittsburgh to Johnstown. The gap between the two canals was the Allegheny Mountains, and it would take one of America’s greatest technological and engineering achievements of the time to surmount that obstacle: the Allegheny Portage Railroad (also a National Park), an incline rail system that could haul canal boats up and over the mountains, taking them out of the water on one side and placing them back in the water on the other. The canal opened in 1834.

To feed water into the canal near Johnstown, the Conemaugh River was used. However, it was soon determined that the river ran too low in dry seasons and that a back-up source of water was needed. The resulting solution was to dam the Little Conemaugh River (aka South Fork Creek) to form the Western Reservoir. The dam itself was called the South Fork Dam. Construction began in 1840, but due to a lack of funding it was not completed until 1853.

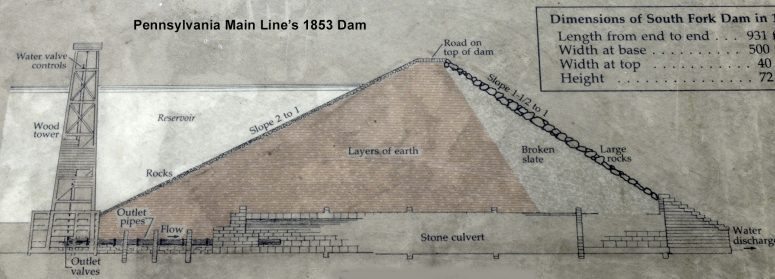

The dam was an earthen dam constructed according to the best engineering techniques of its time. Built in a triangular shape, the base was 500 feet thick while the top, 72 feet high, tapered to 10 feet thick. The dam was made from layers of clay and lined with rock. Five large, cast iron sluice pipes were set into a stone culvert that ran underneath the dam so that excess water from heavy rains could escape. A wooden control tower regulated the flow of the excess water into the sluice pipes. An additional spillway that was ten feet lower than the top of the dam was constructed on the north side. If the excess water could not flow out fast enough, there was still a ten foot margin of safety. The key to an earthen dam is to prevent water from flowing over the top, as that leads to an inevitable collapse.

The South Fork Dam was used by the Pennsylvania Main Line until its demise in 1857. At that time the canal properties were purchased by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which had put the canal out of business (locomotives could now haul goods faster and cheaper than canal boats). Since the Railroad had no real interest in the reservoir, it allowed the dam to decay. In 1862 it collapsed, sending water down the valley towards Johnstown. Luckily the reservoir was not full—the drainage pipes and spillway had released much of the water—and the rivers and streams were running low at the time. While Johnstown was flooded with about three feet of water, no lives were lost and property damage was minimal. After that, the dam was left abandoned for seventeen years.

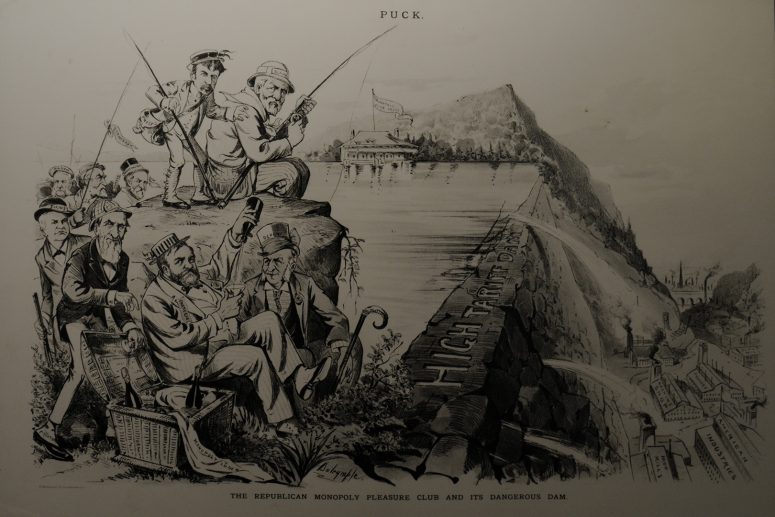

In 1875 the dam was purchased by U. S. Congressman John Reilly. He sold the iron sluice pipes that ran under it, and eventually sold the entire property to Benjamin Ruff in 1879. Ruff had an idea of forming an exclusive resort for the wealthy tycoons of Pittsburgh that would rival the area’s top summer resort in Cresson. What Cresson did not have—a lake—Ruff’s new resort would have. Fishing was just becoming a popular sport, and a lake would certainly draw the wealthy sportsmen away from Cresson. Furthermore, Cresson was a public resort. Ruff’s club would be private and have limited memberships.

Ruff purchased the 500 acres of land for $2,000 (he purchased an additional 124 acres in late 1880). He then proceeded to sell shares in his venture to fifteen other men, including millionaire Henry Clay Frick. A charter was drawn up and submitted for approval in Allegheny County. Pittsburgh was listed as the seat of operation even though the property and actual seat of operation were near Cresson in Cambria County. This was a violation of state law, for organizations had to be chartered in the county where they operated. Nevertheless, it was approved by a judge in November 1879. The new organization was called the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.

The sixteen initial members owned 42 of 100 shares, each priced at $100. The remaining shares were meant for future members, allowing no more than an additional 58 members, or if new members were required to purchase two shares as were the initial members, only 29 new members (the charter was amended in 1881 to allow for more shares). At the time of the flood in 1889, membership stood at 61 men, all from Pittsburgh or Allegheny County, including Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Mellon (Carnegie was also a member of the Cresson resort). Only five of the original members were still in the club at the time.

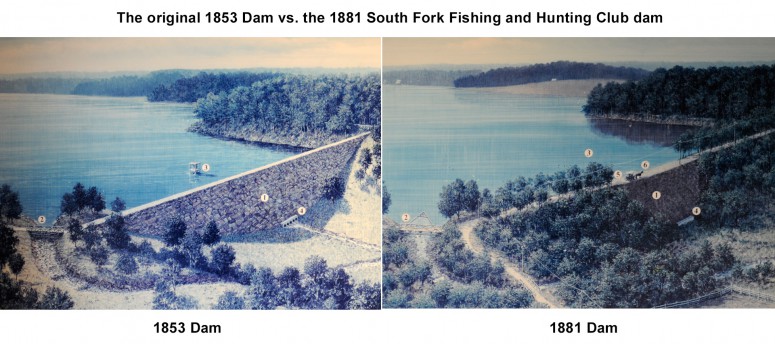

The first order of business was to repair the dam so that a lake, one that would be known as Lake Conemaugh, could be created. Fifty men were hired, but no engineer was consulted about repairing the existing dam. Ruff, now club president, hired a contractor, and though both had a lot of experience in construction, neither knew much about dam building. The original plan was to build a proper dam from the ground up, but when Ruff found out the cost, he opted to repair the existing dam. Unfortunately, his solution was to plug the hole left by the 1862 flood with whatever materials were available, including brush, hay, and manure. Being much looser materials than clay and subject to settling, in later years these materials would cause the center portion of the dam to sag. Corners were also cut when it came to dealing with excess water. The sluice pipes were never replaced, leaving the spillway as the only exit for excess water. It alone was not big enough to deal with the size of the lake that would eventually be created, one much larger and deeper than the Western Reservoir. The new dam was also much thinner: only 270 feet at the base instead of 500 feet as was the 1853 dam.

Further compounding the inadequacies of the repairs, the dam was lowered by three feet to make the top wider so carriages could pass over it. The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club had a staff of chauffeurs who awaited guests at the South Fork rail station and transported them to Lake Conemaugh. To “wow” guests with the grandeur of the surroundings, chauffeurs would take the road over the dam, pausing for a moment so guests could take in the view of the lake. With the top being only ten feet wide, there wasn’t much room for a carriage, let alone two trying to pass each other. Thus, since the dam was shaped like a triangle with the narrowest part at the top, shaving off a few feet would create a wider top surface, thus providing more room for carriages to pass. This also had the inadvertent effect of making the spillway closer to the top of the dam. Excess water that could not escape through the spillway only had to rise seven feet before flowing over the top instead of the previous ten feet.

On Christmas Day 1879, heavy rains washed away all of Ruff’s repair work, and renovation was halted until the following summer. A little over a year later, in February 1881, the same thing happened. Repairs were quickly made again, and the lake began to fill with water. By March it was deep enough to stock with fish, which were brought in by train from Lake Erie. To keep them from escaping down the river, a metal screen was placed at the mouth of the spillway, a decision that would play heavily in the 1889 disaster.

The biggest industrial complex in Johnstown was the Cambria Iron Works. A flood due to a break in the dam would cause a massive financial loss to the company. Because of this, general manager Daniel Morrell sent a team of engineers to inspect the new South Fork Dam. They reported numerous problems with its construction. Benjamin Ruff refuted their findings and asserted that his “engineers” guaranteed that the dam was safe. Morrell sent a reply offering to help make the dam more secure, but Ruff never answered.

Throughout all of this, the club and its members were followed by the local press, the paparazzi of the time. As is the case today, people loved to read about the lifestyles of the rich and famous. However, not only did rumors and facts about the new club and its members make the paper, but so did stories about the damages to the dam and the ill-conceived repair methods. This led the citizens of Johnstown and other low-lying towns to become extremely apprehension. Most everyone still remembered the dam break in 1862. However, as the years wore on, despite rumors during rainy times that the dam was about to break, the citizens of Johnstown became complacent about a potential disaster.

With the lake now completed, construction began on the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club’s first buildings, many of which were completed for the 1881 season. The first to be built was a clubhouse. A guest registry was kept for the 1881 through 1883 seasons, and the first entry was on July 28, 1881, most likely the date when the clubhouse opened. The lower floor was used for social functions and dining, while the upper floor contained guest rooms. Some members elected to build their own “cottages,” which to the average person were large houses. The Pittsburgh Gazette reported that seven cottages had been built by 1883. Overall, sixteen cottages were built. The last structure was completed in 1888. All buildings were connected together by a boardwalk.

Although it was soon evident that the current clubhouse was not large enough to accommodate all members and guests, an addition was not completed until 1886. When finished, the clubhouse had 47 rooms as well as a larger dining area. The building that stands today is the addition. The original clubhouse was attached to the left side of the current structure, but was damaged in a fire and torn down in the late 1930s.

1886 addition to the clubhouse of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, part of Johnstown Flood National Memorial

1886 addition to the clubhouse of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, part of Johnstown Flood National Memorial

In addition to the cottages and clubhouse, boat houses and docks, outhouses (there was no modern plumbing), and storage sheds were built. The last scheduled building project before the dam collapsed was a sewer line for indoor plumbing. On the day of the collapse, club president Elias Unger enlisted a group of Italian immigrants to help save the dam. They were in the area to work on the sewer project. However, no evidence of a sewer—even a partial line—has ever been uncovered.

Members of the club who did not own a cottage were entitled to spend two weeks at Lake Conemaugh each summer season. If rooms were not booked at the time of their departure, they could stay longer. Cottage owners could spend the entire year at the lake if they so desired. Guests could stay no longer than ten days each year. Limits on stays were necessary due to the number of rooms. Furthermore, rules evolved that required members to eat all meals at the clubhouse, though this was not the case in at least the first three seasons (1881-83). A guest log was kept during this time, and whether or not a member dined at the clubhouse was recorded. Members were billed for all services. Guests were not allowed to pay for anything, and any bills they ran up were the responsibility of their hosts.

Activities at the club included hunting, fishing, boating and sailing, swimming, and hiking. The club maintained a fleet of boats, including two steam yachts, four sail boats, and a large number of canoes and rowboats. The final event of the season was a Regatta and Feast of Lanterns.

And so went life at the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club…until the rains began to fall on May 29, 1889.

On the morning of the 31st, Elias Unger woke up to see that Lake Conemaugh had taken on a significant amount of water over night, and the rain was still coming down. Unger became the club’s second president after Ruff died in 1887, and he now lived in a house high on a ridge that overlooked the lake from the north shore. He was not wealthy like the other members, but he had been successful in the hotel business and had become good friends with many of the members. When Ruff died, Unger was considered an excellent replacement, and he was allowed into the club, though management duties were attached to his membership.

Original Unger House overlooks the dry lake bed of the former Lake Conemaugh, Johnstown Flood National Memorial

“It looked as though the whole valley were under water,” Unger would later say. Creeks and streams that flowed into the lake were now rushing with water, carrying with them fallen trees and other debris, all of which flowed towards the spillway, carried by a current generated by the water rushing out of the lake at that point. This presented a catastrophic problem in that the screen that kept the fish in would not let the debris out, and the buildup was now blocking the flow of excess water through the spillway.

Also on hand was a young engineer named John Parke who was on the premises after being hired to install the new sewer system. Parke got in a boat and began taking measurements of the lake and found that it was rising about one foot per hour. Parke would eventually be sent riding towards South Fork to send a telegram to Johnstown warning of the possible danger. Whether or not the message was ever received, and what was done with it, is still unclear to this day. It is only safe to say that the warning was never delivered to the people of Johnstown.

Unger’s first course of action was to clear the debris from the spillway by removing the fish screen. A few club members who were at the lake at the time argued that removing the screen would ruin the fishing on the lake. However, the debate was irrelevant because the debris was now so tightly packed against the screen that it could not be removed. Unger then gathered the Italian immigrants who were camped near the south end of the dam and set them to work digging a new spillway, but it was a matter of too little, too late. The men worked until around 1:30 PM, then retired to higher ground fearing the dam could collapse at any minute. Unger went back to his house knowing what was inevitably going to happen. He lived out the rest of his life at the house, one that would soon be looking over a dry lake bed and broken dam.

Around 3 PM the water began flowing over the top of the South Fork Dam, setting in motion its collapse, and soon a 300-foot gap had been created. Within forty minutes the entire lake had emptied. Twenty million cubic tons of water were now rushing down the valley towards Johnstown. It is staggering to think that water can remove that much earth. When the water is contained within the lake bed, the dam is plenty strong enough to stand up to the pressure, but once it flows over the top, failure is inevitable. The rushing water quickly removes the top layer of the dam, where it is thinnest. From that point a snowball effect begins. As the top of the dam washes away, larger chunks begin to go with it, leaving more gaps for more water to flow through, which in turn takes more earth with it. As it flows down the back side of the dam, the lesser packed materials easily wash away with the water. It is a whittling down of the dam from the top that causes an earthen dam to fail, not the pushing of earth out of the way from a direct, frontal assault.

The following video, though simplistic, demonstrates how the topping of an earthen dam by water causes such as quick collapse (unless you want to see the tank fill with water, skip towards to the end to see the collapse).

It took one hour for the water to reach Johnstown, and on the way it washed away the towns of South Fork, Mineral Point, East Conemaugh, and Woodvale. At Woodvale the waters hit the Cambria Iron Works, taking with it barbed wire, rail cars, and other debris. One witness said the wave didn’t even look like water, but a hill that simply rolled over and over on itself.

All residents of Johnstown were caught by surprise when the water and debris hit the city at 40 miles per hour and with waves topping 60 feet. As debris piled up at the Stone Bridge that crossed the Conemaugh River just north of the city, it created a dam of its own, sending water back into Johnstown and forming a lake over the city. To make matters worse, the debris caught fire. Eighty or so people were washed into the debris field and burned to death. The debris burned for three days, and it took three months to clear it.

Over 2,200 people were killed as a result of the flood. Many bodies were burned and disfigured beyond recognition. Nearly 800 of the dead were never identified and are now buried in Grandview Cemetery in a field of blank tombstones.

An outpouring of aid, both financial and physical, came from around the world as the press spread the word of the disaster, though many of the stories were sensationalized to sell papers. Thousands of dollars in aid came from members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club despite the fact that many victims looked to them as the cause of the disaster. Carnegie and Frick made the highest contributions. All told, nearly $4 million dollars was donated to the relief effort.

In the aftermath, lawsuits were filed against members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, but not one person was found guilty of negligence. In all cases the judge ruled the disaster “an act of God.”

After the flood, club members distanced themselves from the property for legal reasons, abandoning the clubhouse and cottages. By the early summer of 1890, families that were made homeless by the disaster moved into the empty buildings and remained there at least throughout the winter. The families enjoyed the lavish furnishings left behind by the owners; very few owners, if any, came back to get their belongings.

Due to club secrecy, there were no easily available legal records that identified who owned what, and for over a hundred years, tagging owners to homes was done by deduction, assumption, and guessing. Then in 2016, a box of records was found in the attic of the Cambria County Historical Society that identified all cottage owners. The records once belonged to John W. Kephart, an attorney involved with the dissolution of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.

Between 1901 and 1902, club members deeded all property to the club’s trustee, A. B. Alsop, so that everything could be sold as one unit. In February 1903, George Harshberger purchased the property, then sold off bits and pieces over the next few years. In 1904 he held an auction for the contents of the clubhouse, which included 50 bedroom suites, silver and tableware, carpet, and furniture. Many people came to purchase items for their historical value.

The cottages were eventually sold to the Maryland Coal Company in 1907. Coal was discovered in the dry lake bed, and the town of St. Michael sprang up from this coal mining operation. The cottages were used for company housing, though many were torn down over the years and replaced with new buildings, some of which were also used for company housing. Today there are houses on many of the lots that were once owned by South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club members. The original cottages are marked with a plaque on the front of the house.

Home built in 1885 by South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club member J. J. Lawrence, now part of the St. Michael Historic District

The cottages and land remained with the Maryland Coal Company until 1933, at which time the property was sold to the Wilmore Coal Company. Wilmore in turn sold the property to the Berwind-White Coal Company in 1955. All of the coal companies used the cottages for company housing. All housing units—original cottages and newer company houses—were eventually sold to private citizens in the mid-1950s, some of who were company employees that had been living in them for years. Today, along with the clubhouse addition from 1886, nine cottages still remain standing. Six are now privately owned. The other three are owned by the National Park Service.

The clubhouse and 30 acres were purchased by John Sechler in 1907. He operated a hotel from the building until 1920 when he lost it to foreclosure. From 1921 until 1950 it was owned by the Cruikshank family, who also used it as a hotel. It was during this time that the original clubhouse was damaged by fire and torn down (late 1930s). The Cruikshanks sold the building to Albert and Lucy Clement, and they operated it as the Clement Hotel until 1958. It remained in use since then as a hotel, boarding house, and even a biker bar until being purchased in the early 1990s by the 1889 South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Preservation Society. The Preservation Society also purchased two cottages, the Brown Cottage and the Double Cottage (owned by four club members). Renovations were made throughout the 1990s as funding allowed. In 2006 the clubhouse and the two cottages were donated to the National Park Service. The National Park Service has since acquired one other building, the Lippincott Cottage, the largest of all cottages built by club members.

A new front porch was part of earlier renovations to the clubhouse of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, Johnstown Flood National Memorial

One of the cottages owned by the National Park Service is the Double Cottage, which was built jointly by four club members in 1887. Prior to 2016, this building was believed to have been built by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club itself to house guests when all the clubhouse rooms were filled. However, the records discovered in 2016 revealed that this was one of the sixteen private cottages built by club members. The building contains four, two-bedroom apartments.

The Double Cottage once owned jointly by four South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club Members is now owned by the National Park Service and is part of Johnstown Flood National Memorial

Johnstown Flood National Memorial was created in 1964. It currently preserves the South Fork Dam ruins and a few of the historic buildings at St. Michael. For a more complete picture of the flood, those with time may want to venture to Johnstown and visit the Johnstown Flood Museum and the Grandview Cemetery. See the Related Sites web page here on National Park Planner for more information.

The following video was created for a seventh grade National History Day documentary project about the 1889 Johnstown Flood in Pennsylvania. It does a decent job of covering the basic history of the flood.

With a few exceptions, use of any photograph on the National Park Planner website requires a paid Royalty Free Editorial Use License or Commercial Use License. See the Photo Usage page for details.

Last updated on April 8, 2025