A common misconception about the American Revolution is that all colonists were in favor of independence from England. While it is impossible to say for sure, historians conclude that only about 20% of the “American” population (the term American wasn’t coined at the time) wanted independence, while 20% did not. The rest didn’t care one way or another and were basically bandwagon fans—whoever was winning at the time, that’s who they supported. They didn’t want to end up on the wrong end of a hangman’s rope for being on the losing side.

If only 20% of the population was gung-ho about independence, it stands to reason that only a small number of the politicians were gung-ho as well. Most were, in fact, level-headed men who wanted to work out some sort of compromise with England, using war as a last resort. Such a man was Thomas Stone.

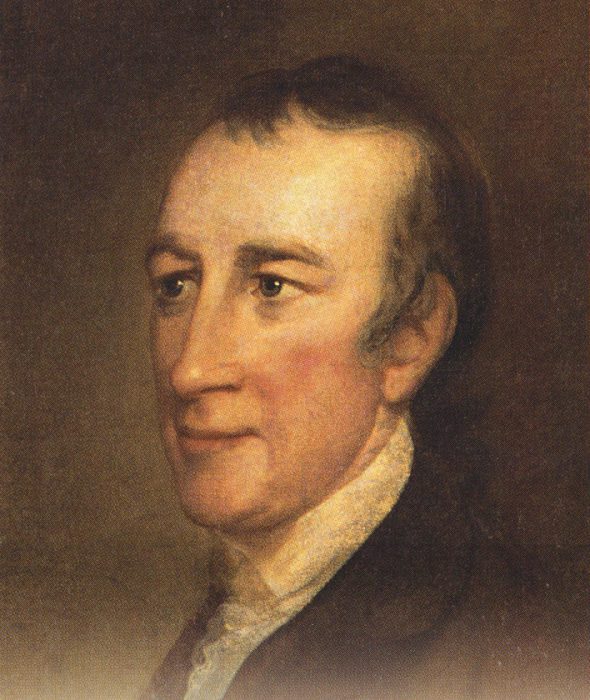

Stone was born in the colony of Maryland in 1743 to a well-to-do family. His grandfather had been governor of Maryland, so politics and public service were nothing new to him. He excelled in school, and upon finishing he took up the study of law, and that is the profession he eventually entered into by 1765.

In 1771, at the age of 28, Stone married Margaret Brown. At the time dowries were in fashion, and Stone received £1,000 from Margaret’s father, Gustavus Brown. With this money he purchased the estate known today as Haber de Venture, which is the heart of Thomas Stone National Historic Site. While he ran a small plantation and raised livestock on the property, the estate served primarily as his residence. He lived at Haber de Venture with his wife and three children until moving to Annapolis in 1783, though he retained ownership of the plantation. The property remained in the Stone family until being sold in 1936.

Stone first entered public service in 1774 when he was elected a member of the Charles County Committee of Correspondence, an organization that maintained contact with the other colonies. A year later he was chosen to represent Maryland in the Second Continental Congress held in Philadelphia. The Continental Congress was put together by those known as Patriots—proponents of independence from England—to govern the thirteen colonies when trouble first began brewing. The First Continental Congress met in 1774, while the Second was called together in May 1775. It was the Second Continental Congress that voted on independence.

The citizens of Maryland were, on the whole, loyal supporters of the King, and the Maryland Convention (the colony’s governing body) that elected Stone and three other delegates to Congress—William Paca, Samuel Chase, Charles Carroll—forbade them to sign any declaration of independence unless it was the very last option on the table. Furthermore, if all other colonies voted for independence and Stone and his fellow statesmen were against it, they were to leave Congress and return to Maryland so that the matter could be discussed by the Convention. However, by the spring of 1776, the Maryland Convention had an abrupt change of heart after realizing the King of England had no intention of compromising. Colonies had been declaring independence since April 12th when North Carolina instructed its delegates to vote for independence. Maryland did the same on June 28th.

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted for independence; no delegates voted against the measure (New York did not vote). The final version of the Declaration of Independence, which had been in the works since June 11th in anticipation of this moment, was presented to the states on July 4th, the day now celebrated as America’s Independence Day. By virtue of being a member of the Second Continental Congress, Thomas Stone became one of the fifty-six men to sign the document.

The newly formed country now needed a constitution, and Stone was appointed as the Maryland delegate to the task. It took until November 1777 to finalize what became the Articles of Confederation, the first constitution of the United States. (Stone was a signer on an early version, but not on the final version.) With that done, Stone exited Congress and focused on state politics, with most of his efforts being put toward getting reluctant Maryland politicians to ratify the document. During this time he was re-elected to Congress, but declined. It would take until March 1, 1781 for all thirteen states to ratify the Articles of Confederation—Maryland was the last state to approve. Unfortunately, the new constitution limited the power of the federal government and ultimately proved ineffective. In 1786, talks of drafting a new constitution began circulating. Thomas Stone would not live to see the results.

The Third Continental Congress—now called the Confederation Congress—was convened in 1781. Stone was once again elected a member in 1783 and this time accepted, taking his seat when the session began in March 1784. However, this was to be his last stint in the federal government, and in 1785 he returned to practicing law and participating in local politics, and more importantly, taking care of his very sick wife.

In 1776, Margaret was inoculated for small pox and had a devastating reaction to the mercury used in the vaccine. Her health quickly declined and she eventually became an invalid, spending most of the last decade of her life in bed. Things took a turn for the worse in the spring of 1787, and on June 3, Margaret died at the age of 36. Four months later on October 5th, so distraught over his wife’s death that he failed to care for his own health, Thomas died suddenly in Alexandria, Virginia, while preparing for a much needed vacation to England. Both he and Margaret are buried in the family cemetery at Haber de Venture.

With a few exceptions, use of any photograph on the National Park Planner website requires a paid Royalty Free Editorial Use License or Commercial Use License. See the Photo Usage page for details.

Last updated on April 19, 2020